Tahchin with fried brinjal (Tahchin-e badenjan)

4–6

4–6

Easy

Easy

2 hours

2 hours

For a lavish, fragrant and highly celebratory dish that is usually prepared for gatherings or ordered in restaurants, tahchin is relatively easy to make. The rice is parboiled, but is kept a little more al dente, because its second cooking (steaming or ‘brewing’) will be in a batter of yoghurt and eggs, spiked with saffron and freshly ground black pepper.

Tahchin gets its name from laying pieces of either lamb, chicken or condiments at the bottom of a cooking pot. But don’t confuse it with tahdig, which is literally the crust at the bottom of a pot of rice, and can be made with anything from plain rice to slices of potato, flat bread or pumpkin (winter squash), and even lettuce (not a favourite of mine). Tahchin is always a rice cake that, when unmoulded, keeps the shape of its container, thanks to the batter of yoghurt and eggs. And there’s always a stuffing of meat, poultry or vegetables. Amazingly, it looks a lot like another lavish rice cake from Naples, called sartù di riso, which hails from a time when cooks of the court were challenged to come up with a rice dish delicious enough to satisfy the maccheroni loving Neopolitan royals — a dish in which the rice is also held together with a batter of eggs and parmesan, encasing a filling of ragù and fried meatballs, and sometimes aubergine or other ingredients.

One of the finest tahchins in Iran uses large pieces of delicate, fatty lamb neck or shoulder, marinated overnight in yoghurt and saffron, as a filling. But I find tahchin is a wonderful way to turn leftover meat — particularly from roasts — into another marvellous dish; think of the salvation it can be after Thanksgiving or Christmas, or how it can give another life to the meat from that chicken you’ve boiled for several hours simply to make a broth or stock.

Vegetarian tahchins, although not an innovation, are more uncommon. The one opposite with fried aubergine is an absolute delight, but you can easily use marrow or pumpkin (winter squash) instead. The point is, just about any ingredient, if properly flavoured, can make an excellent filling for a tahchin.

One last tip: the barberry garnish may seem fussy or unnecessary, but those tiny pockets of pure acidity work wonders in your mouth against the rich, eggy and fatty rice. Don’t skip them. While I have been known to voice strong feelings against topping random dishes with pomegranate seeds in the name of making them ‘Persian’, for this particular recipe, if you can’t find barberries, a fistful of raw pomegranate seeds added right before serving will do the job, and look quite festive too.

Ingredients

Method

-

For the rice:

- 1¾ cups Iranian or basmati-style long-grain rice

- 70 g coarse salt

- 1½ t vegetable oil For the saffron infusion:

- ½ t saffron threads, very loosely packed

- a good pinch of sugar For the tahchin:

- 1 kg brinjals, peeled and sliced 1 cm thick

- vegetable oil, for shallow-frying brinjal

- ¼ t ground turmeric

- 200 g plain Greek-style yoghurt (or strained yoghurt)

- 3 eggs

- 45 ml saffron infusion

- ½ t salt

- ¼ t freshly ground black pepper

- 50 g ghee (or half butter, half oil)

- ½ t ground cinnamon

- 2 T golden onion For garnishing:

- 4 T dried barberries

- 1 t butter

- ½ t sugar

Method

Ingredients

1. At least 2–3 hours before you want to serve the dish, gently rinse the rice with cold water, discarding the water. Do this at least three times. The water will always remain a bit cloudy, but rinsing removes the excess starch from the rice, which will make the rice fluffy once cooked, with each grain separated.

2. Add the rice to a large bowl, with enough water to cover the rice by at least 5 cm. Add the salt and fold gently, possibly with your hand. Taste the water: it should be as salty as the sea. Don’t worry if the water seems too salty — the rice absorbs the salt it needs, and any excess salt can be rinsed away after the first cooking (the parboiling stage). Soak the rice for 2–3 hours, or at least 30 minutes. You can even soak the rice overnight.

3. Meanwhile, make the saffron infusion, grind the saffron strands with the sugar in a small mortar. If you don’t have a small mortar, you can put the saffron and sugar on a piece of baking paper, fold all the sides so the powder won’t escape, then grind with a jam jar or rolling pin until you have a very fine powder.

4. Boil the kettle, then let it sit for a few minutes. Tip the powder very gently into a small glass teacup, then gently pour 3 tablespoons of the hot water over it. (Never use boiling water, or you’ll ‘kill’ the saffron.) Cover the cup with a lid or saucer and let the mixture ‘brew’ for at least 10 minutes without removing the lid, to release the colour and aroma of the saffron. After this time your saffron infusion is ready to use.

(If you make a larger batch, store the leftovers in a clean sealed jar in the fridge for 4–5 days. You can also make a refreshing drink called a sharbat with any leftover saffron infusion, or add it to your regular cup of tea.)

5. Then, rub the aubergine slices with salt and leave in a colander in the sink for at least 30 minutes to drain off any bitter juices. Rinse with water, then pat dry with paper towel. Heat a few tablespoons of frying oil in a frying pan (the quantity you’ll need depends on the size of your pan). In batches, fry the aubergine slices over high heat for a few minutes on each side until golden; it doesn’t matter if the centre seems uncooked, as the aubergine will cook through in the rice later.

6. Lay the fried aubergine in a dish lined with paper towel to absorb the excess oil, and sprinkle the turmeric on top. In a large bowl, mix the yoghurt with the eggs, saffron infusion, salt and pepper. If the yoghurt is too thick, add a splash of water. Discard the water from the soaking rice, then parboil the rice.

Parboiling the rice

7. Bring a large pot of water to the boil. Add 1 T vegetable oil. Discard most of the soaking water from the rice, without draining it completely, then gently add the rice and what’s left of the soaking water to the boiling water. Do not stir the rice too much, or you’ll break the grains. If needed, put the lid on to bring the water back up to the boil as quickly as possible. We want to partially cook the rice at this point; meaning the grains will swell, and the outer part of the grain should be soft, but a bit of a bite should remain in the centre (similar to very al dente, if we were talking about pasta).

8. The parboiling time varies depending on the quality of rice, and even the humidity of the region in which you live. For the tahchin, cook the rice for a shorter time so that it is a little more al dente than usual. For some types of basmati rice, this will take only a couple of minutes; others can take up to 10 minutes. Drain and rinse the rice by placing a fine-meshed colander in your kitchen sink, then very gently and carefully drain the rice into the colander. Taste the rice. If it’s too salty (it shouldn’t be), run cold water over the rice for several minutes. Otherwise, run the cold tap water for only about 30 seconds, just to stop the cooking process.

Gently fold the rice into the bowl of saffron yoghurt.

9. In a 23–28 cm non-stick, heavy-based pot, heat the ghee over high heat. When it’s really hot, add half the rice and yoghurt mixture and gently push down with the back of a spoon. Cover with half the aubergine slices, sprinkle with the cinnamon and golden onion, then cover with the remaining aubergine. Finally, add the remaining rice mixture and push it down. Wrap the lid with a clean tea towel and place it on the pot, ensuring it seals well. After 5–10 minutes over high heat, reduce the heat to the lowest setting; ideally, use a heat diffuser here. Cook — without ever lifting the lid — for 80–90 minutes. Turn the heat off and let the tahchin rest for 5 minutes.

10. While the tahchin is resting, rinse the barberries and place in a small saucepan. Cook them with the butter over medium–low heat for a minute or two. Add the sugar, stir them around a bit, then immediately turn off the heat so the sugar doesn’t burn.

Turning out the Tahchin

11. Now let’s flip the tahchin onto a large serving plate. This part is a bit tricky, and everything is very hot, so be careful. Remove the lid and place your serving plate (which should be flat, and a bit larger than the pot) upside down over the pot. Using oven mitts or pot holders, hold the pot handles and the dish together, then flip the pan over in one movement and put them on the counter or a table. Gently remove the pan. Your tahchin should be inverted onto the serving plate like a nice saffron cake. Pile the barberries (or raw pomegranate seeds) in the centre of the tahchin.

12. Cut into slices to serve, possibly with salad Shirazi or yoghurt, although these aren’t strictly necessary.

Cook's note: You can also bake tahchin in the oven, either in a tall baking dish, or preferably in a cast-iron pot — although, being heavy, it’ll make the tahchin harder to flip. The important thing is to have the oven preheated to 180°C (350°F), and have both the baking dish and the oil very hot before starting to layer in the rice and filling. Seal tightly with a lid or foil and bake for 80–90 minutes.

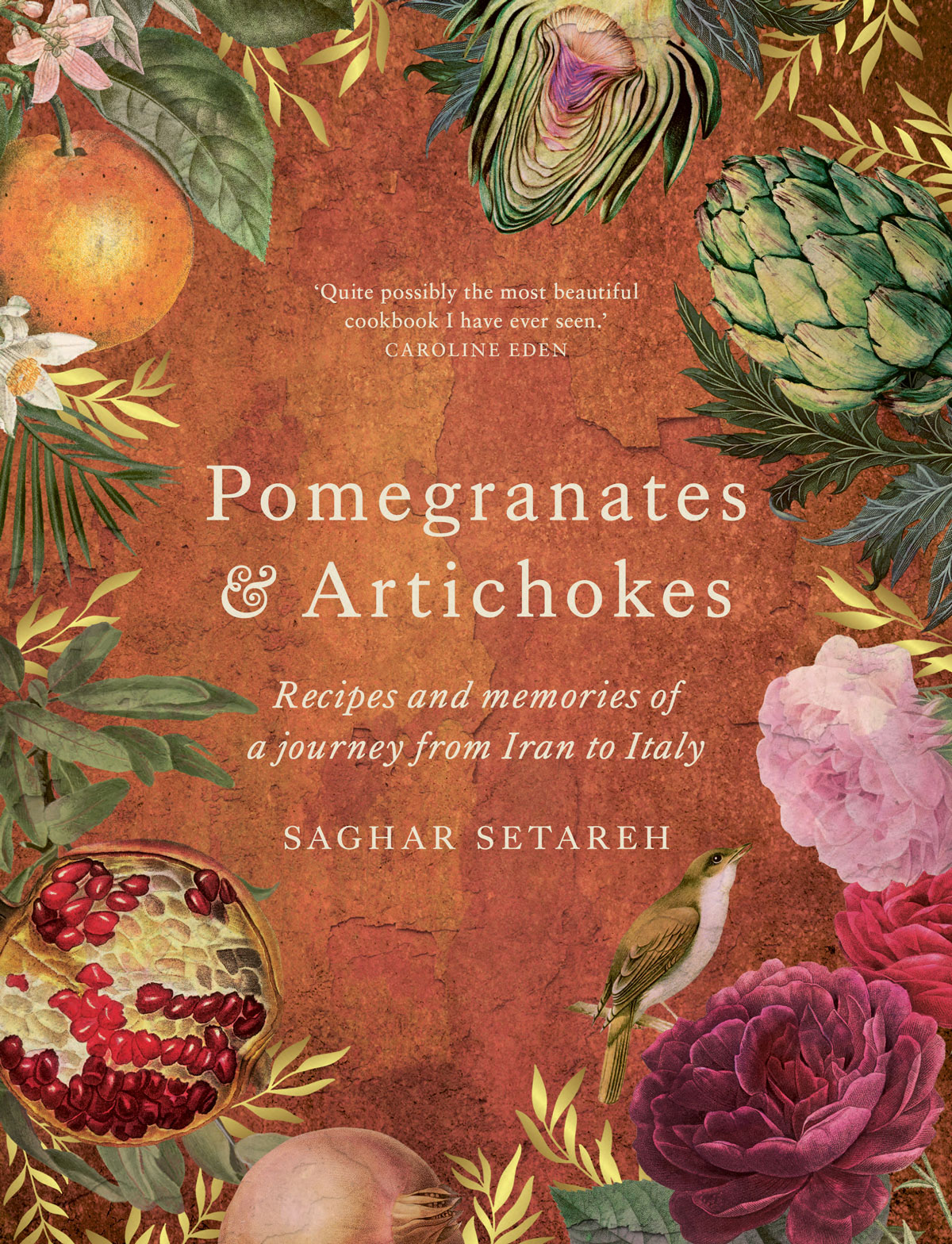

This is an extract from Pomegranates + Artichokes: Recipes and memories of a journey from Iran to Italy by Saghar Setareh (Murdoch Books). Photography by Saghar Setareh

There are no comments yet.