How learning to make curry forced me to face my heritage

Despite loving curry, TASTE online editor, Annzra Denita Naidoo refused to learn how to make it. It wasn’t until lockdown that she finally caved and asked her dad to teach her. But the experience made her confront parts of herself she never thought it would.

Food is important. It’s nostalgic, cultural, political, experimental, educational and, most importantly, a form of self-expression. This is especially true when it comes to cultural food. I often see how passionately people speak about food from their heritage on TASTE’s social media channels. These range from debates on whether we’ve done justice to recipes, to expressions of joy at being represented. I, as a South African Indian, have always loved the food of my heritage. But I’ve not always loved my heritage. It's something I had to face in 2020, and it came to me in the form of a Durban curry.

Four years ago, I wrote a column about setting up my spice cupboard for the first time. In that column, I mentioned how I wasn't interested in learning how to make curry when I was younger, and that I would tell that story on another day. It proved to be more difficult than I thought (hence the years between these columns 😅). This is because I had to explore WHY I didn’t want to learn.

ALSO READ: The nostalgic, but slightly terrifying, task of setting up my first spice cupboard

My love/hate relationship with my heritage

In my teenage, bratty days, I would arrogantly declare that the only good things about my heritage were its food and fashion. I truly believed this. I loved how colourful our sarees, lehengas and punjabis were. And the jewellery! Gosh, so beautiful. I always loved Indian food. It’s bold, flavourful and full of history. But, as an introverted, geeky, Catholic, only child who grew up in a small Afrikaans town far from my extended family, I felt so removed from my heritage as a whole.

I sang "Vader Jakob" and "Jan Pierewiet", while my cousins sang English nursery rhymes (my family lost our Tamil language generations ago). I read fantasy books, watched too much TV, and kept to myself. My family didn’t really talk about race or culture (they were still processing the post-apartheid world), so I wasn’t curious about my heritage. Even the rare occasions when I went to the temple with my Ma (grandmother) didn’t pique my interest. I was really just there for the food after the poojas.

As I grew older, these factors made me feel like I had slipped through the cracks. I was often the only Indian kid at school, which made me decidedly different. And my lack of exposure to other Indian people meant I was not “Indian enough” when I entered those spaces. Non-Indians expected stereotypical things from me. Indians teased me for being different or unaware. It was infuriating. It made me hate my cultural identity. I wanted to distance myself from it. I could never be ashamed of our food; it was just too delicious, but I could refuse to learn about it. That was my act of rebellion.

ALSO READ: How cooking East Asian food (kind of) made my dreams come true

Learning to make curry in lockdown

It took many years, tough conversations and therapy to get over my internalised racism. We don’t have to get into it all here, but I assure you I did the work and now see that light. But throughout my 20s, I still didn’t bother to learn how to make curry. I didn’t need to. Trips home or to my family meant I got to eat lots of it. When I couldn’t wait for home food, I could buy curry. Granted, most of the curry in Cape Town is Cape Malay style or Indian (as in from the continent). Durban-style curry is rare, but Curry Quest in Mowbray solved that issue. It’s a firm favourite of mine and was started by Durbanite Vani Moodley.

Indian lamb on the bone recipe

But then lockdown happened. All the restaurants were shut down. I couldn’t travel back to Joburg, where my parents live. I craved home, family and comfort. The closest thing I could think of to alleviate this was a nice, hot curry, with gravy-soaker potatoes and rice I ate with my hands. But I didn’t know how to make it.

It hit me like a ton of bricks. My act of rebellion was a silly one, and it only caused me harm. Here I was, yearning for a vital piece of my culture, but I couldn’t have it. I had selfishly cut myself off from something I loved that was clearly important to me. And the worst part? It didn’t really make a difference. People still make stereotypical assumptions about me, and people of my culture still tease me. The only difference is now, I’m not bothered by it. But I was bothered that I did not know how to cook curry. Thus, I set out on a mission to learn.

ALSO READ: Social media made me do it: how “FoodTok” influenced my cooking

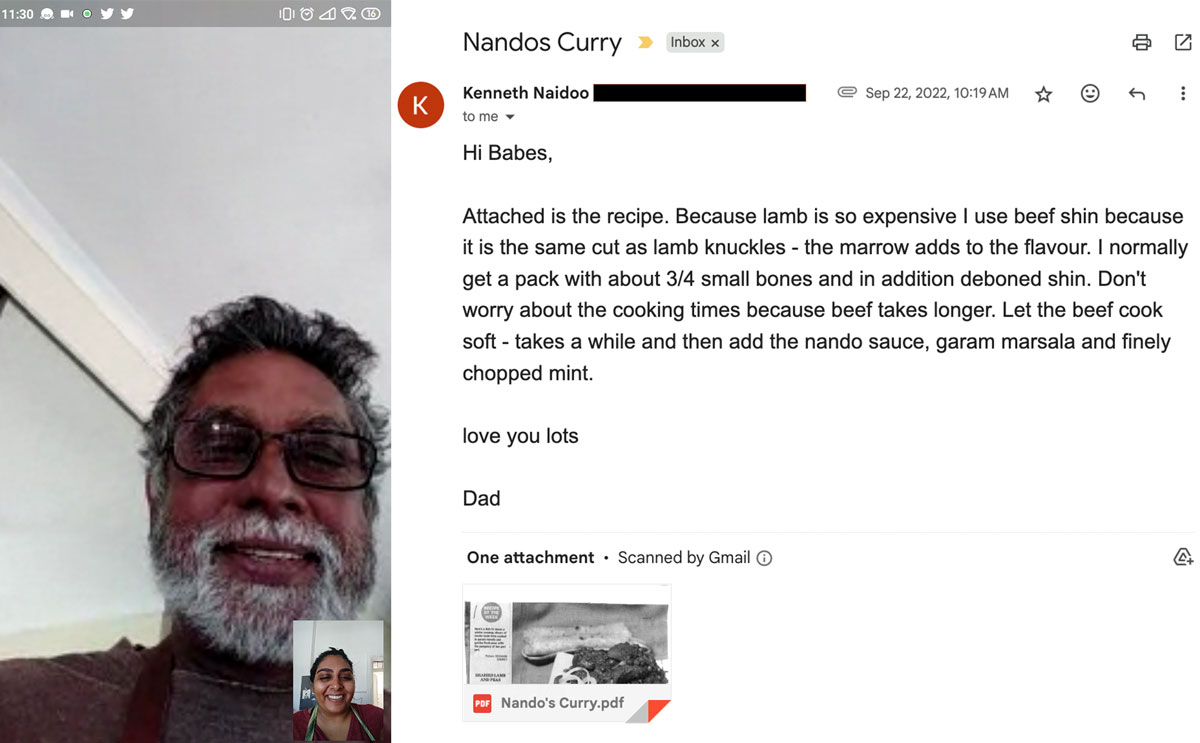

First, I tried using a recipe. But my potatoes turned to mush and my chicken fell off the bone (not in a good way). I needed guidance. So I turned to the person who had ignited my love of cooking. My dad. He shared his tried-and-trusted recipes with me, including easy "cheat" recipes to boost my confidence. He scanned his favourite recipes from cookbooks and old newspaper clippings and emailed them to me. These included his favourites, The Masala Cookbook by Parvati Narshi and Ben Williams – a mother- and son-in-law team from Cape Town, and old clippings from Asha Maharaj’s Sunday Times feature called Ask Asha. He even typed out his own recipes for me whenever I called asking how to make something. He continues to do this to this day.

ALSO READ: How to make South African curry

But that’s not all. When I started out back in 2020, Dad would video call me to make sure I was doing everything correctly. He inspected the ingredients, timed how long I fried the onions, and checked how much water I added. There was a little bit of shouting (which gave me slight PTSD from when he tried to teach me maths), but overall, I loved the experience.

My first few attempts tasted okay. I always panicked when it came to adding the potatoes. Was it too soon? Too late? How would I know when it was ready? But the more I practised, the better I got, and the more confident I became. I jokingly told my friends that I’m turning into an aunty, and I actually love this version of me.

BTW, my dad also coached me through making biryani during lockdown, which I made for Easter 2020. Spoiler alert, I had a potato issue (it’s always the potatoes… sigh), but I course-corrected and it turned out okay.

ALSO READ: I got an air-fryer and it did not change my life

Finding more inspiration

No one makes curry the exact same way. So I knew I had to expand my sources to figure out my own style. When my cousin Santo came to visit me, I noted how much oil and masala she used. I called my Aunty Maliga, the queen of mutton curry in my family, to learn how she makes her curry. My mom learnt how to make vegetable curries from her mother-in-law, who was a master at it. Mom passed down Grandma’s mantra – cook it low and slow.

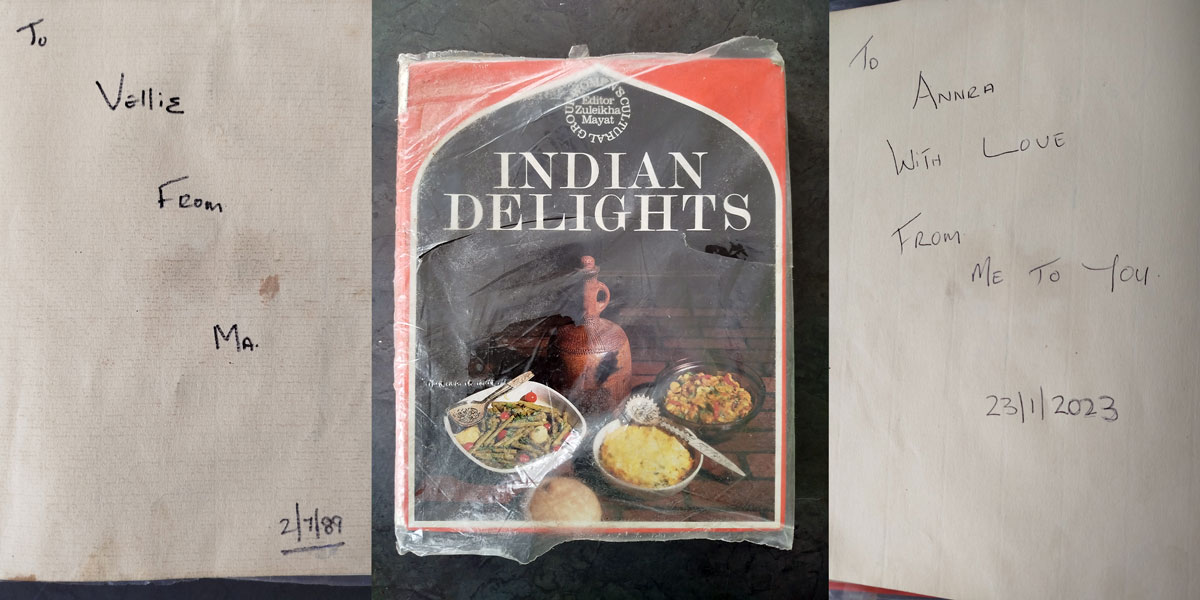

Mom also passed on the quintessential South African Indian cookbook to me: Indian Delights by Zuleikha Mayat. Her mother gave her the book in 1989 (a year before I was born), and she passed the book on to me in 2023. I also turned to Ishay Govender’s outstanding book Curry, which shares recipes and stories from across South Africa.

Will I make you curry?

It depends. I’m confident with my lamb and mince curry, but still a little nervous with chicken. I can make a half-decent veg curry (green bean curry and curried cabbage are my favourites), but I have to be more patient to perfect it. So you may get curry, but note, I’m just five years into my curry education and still have a lot to learn. I’m proud of the progress I’ve made and how this process has given me new respect and love for South African Indian culture. I’m not sure how teenage me would feel about this move, but I’m sure if I gave her a plate of home-made curry, she’d happily eat it. After all, one of the best things about my culture is our food.

Comments